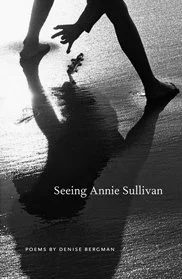

SEEING ANNIE SULLIVAN

Some of us blunder into life through the back door.

—Annie Sullivan

Seeing Annie Sullivan approaches sight on multiple levels. One sees—quite literally, in beautiful poetic evocation—this great teacher's early years. One sees as she saw and as she taught her famous pupil to see: substituting sensibility for vision and channeling life's need and energy into an all but impossible task. These poems are marvelous and their composite a gift.

—Margaret Randall

With a delicacy of language and craft, Denise Bergman creates and recreates the life of Annie Sullivan, her early years, her passions for light and its textures, in spite of her ever-present darkness. The poems evoke a life of incredible courage as well as of hope. Bergman's extraordinary poems translate darkness into light.

—Marjorie Agosin

Review by Kimberly Bird in Monthly Review.

Read Denise Bergman's Keynote presentation of Seeing Annie Sullivan at the conference for Talking Book librarians hosted by Perkins School for the Blind in June 2014

Seeing Annie Sullivan was translated into Braille and into a Talking Book. Contact Perkins School for the Blind Braille and Talking Book Library.

To order book contact the author:

denise (at) denisebergman (dot) com

PREFACE

Some of us blunder into life through the back door.

– Annie Sullivan

As the train speeds south, the young woman turns her head to watch the fields and towns pass by. The windows are grimy from years of cigar and cigarette smoke and caked on the outside with dust from the clay earth. Some don't open. Some don't close. Her father had once told her that back in Ireland landlords charged rent by the number of windows, so families boarded them up and lived without air, without light.

The blistering circumstances of her awful childhood was a secret Annie Sullivan kept even from Helen Keller, her student and later her friend, until shortly before she died. The "shame" of poverty that humiliated her as she stood at the entrance to the school for the blind and discovered that, to some, the world she came from was invisible, only fueled her anger toward the injustices among which she had lived and the society that enforced them. "The world of the disinherited," she said, "is one of strangeness, grotesqueness and even terribleness, and a close recital of the doings of its inhabitants reveals an almost new universe." Annie's self-identity as a disinherited person and her sense of being one of the vast number of "undeserving" haunted her throughout her life and might have prevented her from revealing her past.

By nature she was a conceiver, a trailblazer, a pilgrim of life's wholeness.

– Helen Keller

In her time, and over time, Annie Sullivan has been recognized as an innovative and inspired teacher. But the immensity of her contribution to education is, like so much of her life, often obscured by Helen Keller's fame, or miniaturized into simplistic vignettes. Her method of teaching young Helen, making nature and everyday experience the classroom, foreshadows today's progressive education.

When Annie was a student at the Perkins Institution for the Blind, the girls took turns sharing a room with Laura Bridgman, a deaf and blind woman who had been taught by Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe to communicate using the manual alphabet. Later, when Annie was offered the job of teaching Helen Keller in Tuscumbia, Alabama, she read Howe's notes in preparation. Once she became the primary caregiver and teacher of this "wild" and willful girl, her curiosity and instincts about the needs of the moment guided her.

"What a marvelous thing is language!" Annie Sullivan said, "How seldom we give it a thought! Yet it is one of the most amazing facts in life. By means of the spoken or written word, thought leaps over the barrier that separates mind from mind. . . . To think and speak, have ideas and write them, to make plain to others, to talk with strangers . . . to keep [memories of the dead] alive — surely this is the marvel of existence."

—Denise Bergman